This experiment is one of my favorites in this acceleration series, because it clearly shows you what acceleration looks like.

This experiment is one of my favorites in this acceleration series, because it clearly shows you what acceleration looks like.

The materials you need is are:

- a hard, smooth ball (a golf ball, racket ball, pool ball, soccer ball, etc.)

- tape or chalk

- a slightly sloping driveway (you can also use a board for a ramp that’s propped up on one end)

For advanced students, you will also need: a timer or stopwatch, pencil, paper, measuring tape or yard stick, and this printout.

Grab a friend to help you out with this experiment – it’s a lot easier with two people.

Are you ready to get started really discovering what acceleration is all about?

Here’s what you do:

Please login or register to read the rest of this content.

Please login or register to read the rest of this content.

Gyroscopes defy human intuition, common sense, and even appear to defy gravity. You’ll find them in aircraft navigation instruments, games of Ultimate Frisbee, fast bicycles, street motorcycles, toy yo-yos, and the Hubble Space Telescope. And of course, the toy gyroscope (as shown here). Gyroscopes are used at the university level to demonstrate the principles of angular momentum, which is what we’re going to learn about here.

Gyroscopes defy human intuition, common sense, and even appear to defy gravity. You’ll find them in aircraft navigation instruments, games of Ultimate Frisbee, fast bicycles, street motorcycles, toy yo-yos, and the Hubble Space Telescope. And of course, the toy gyroscope (as shown here). Gyroscopes are used at the university level to demonstrate the principles of angular momentum, which is what we’re going to learn about here.

Let's take a good look at Newton's Laws in motion while making something that flies off in both directions. This experiment will pop a cork out of a bottle and make the cork fly go 20 to 30 feet, while the vehicle moves in the other direction!

Let's take a good look at Newton's Laws in motion while making something that flies off in both directions. This experiment will pop a cork out of a bottle and make the cork fly go 20 to 30 feet, while the vehicle moves in the other direction!

Every wonder why you have to wear a seat belt or wear a helmet? Let's find out (safely) by experimenting with a ball.

Every wonder why you have to wear a seat belt or wear a helmet? Let's find out (safely) by experimenting with a ball.

This is a quick and easy demonstration of how to teach Newton’s laws with minimal fuss and materials. All you need is a wagon, a rock, and some friends. We’re going to do a few totally different experiments using the same materials, though, so keep up with the changes as you read through the experiment.

This is a quick and easy demonstration of how to teach Newton’s laws with minimal fuss and materials. All you need is a wagon, a rock, and some friends. We’re going to do a few totally different experiments using the same materials, though, so keep up with the changes as you read through the experiment.

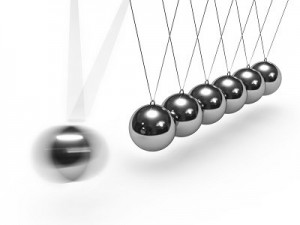

This experiment is for advanced students.It’s time for the last lesson of mechanics. After all this time, you now have a good working knowledge of the rules that govern almost all movement on this planet and beyond!! This lesson we get to learn about things crashing into one another!! Isn’t physics fun?! We are going to learn about impulse and momentum.

This experiment is for advanced students.It’s time for the last lesson of mechanics. After all this time, you now have a good working knowledge of the rules that govern almost all movement on this planet and beyond!! This lesson we get to learn about things crashing into one another!! Isn’t physics fun?! We are going to learn about impulse and momentum.

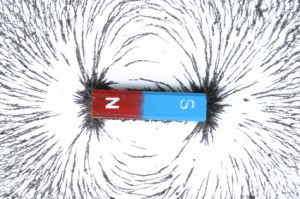

The electromagnetic field is a bit strange. It is caused by either a magnetic field or an electric field moving. If a magnetic field moves, it creates an electric field. If an electric field moves, it creates a magnetic field.

The electromagnetic field is a bit strange. It is caused by either a magnetic field or an electric field moving. If a magnetic field moves, it creates an electric field. If an electric field moves, it creates a magnetic field.

You are actually fairly familiar with electric fields too, but you may not know it. Have you ever rubbed your feet against the floor and then shocked your brother or sister? Have you ever zipped down a plastic slide and noticed that your hair is sticking straight up when you get to the bottom? Both phenomena are caused by electric fields and they are everywhere!

You are actually fairly familiar with electric fields too, but you may not know it. Have you ever rubbed your feet against the floor and then shocked your brother or sister? Have you ever zipped down a plastic slide and noticed that your hair is sticking straight up when you get to the bottom? Both phenomena are caused by electric fields and they are everywhere!

Did you know that your cereal may be magnetic? Depending on the brand of cereal you enjoy in the morning, you’ll be able to see the magnetic effects right in your bowl. You don’t have to eat this experiment when you’re done, but you may if you want to (this is one of the ONLY times I’m going to allow you do eat what you experiment with!) For a variation, pull out all the different boxes of cereal in your cupboard and see which has the greatest magnetic attraction.

Did you know that your cereal may be magnetic? Depending on the brand of cereal you enjoy in the morning, you’ll be able to see the magnetic effects right in your bowl. You don’t have to eat this experiment when you’re done, but you may if you want to (this is one of the ONLY times I’m going to allow you do eat what you experiment with!) For a variation, pull out all the different boxes of cereal in your cupboard and see which has the greatest magnetic attraction.

Find a smooth, cylindrical support column, such as those used to support open-air roofs for breezeways and outdoor hallways (check your local public school or local church). Wind a length of rope one time around the column, and pull on one end while three friends pull on the other in a tug-of-war fashion.

Find a smooth, cylindrical support column, such as those used to support open-air roofs for breezeways and outdoor hallways (check your local public school or local church). Wind a length of rope one time around the column, and pull on one end while three friends pull on the other in a tug-of-war fashion.

Hovercraft transport people and their stuff across ice, grass, swamp, water, and land. Also known as the Air Cushioned Vehicle (ACV), these machines use air to greatly reduce the sliding friction between the bottom of the vehicle (the skirt) and the ground. This is a great example of how lubrication works – most people think of oil as the only way to reduce sliding friction, but gases work well if done right.

Hovercraft transport people and their stuff across ice, grass, swamp, water, and land. Also known as the Air Cushioned Vehicle (ACV), these machines use air to greatly reduce the sliding friction between the bottom of the vehicle (the skirt) and the ground. This is a great example of how lubrication works – most people think of oil as the only way to reduce sliding friction, but gases work well if done right.

Sound is everywhere. It can travel through solids, liquids, and gases, but it does so at different speeds. It can rustle through trees at 770 MPH (miles per hour), echo through the ocean at 3,270 MPH, and resonate through solid rock at 8,600 MPH.

Sound is everywhere. It can travel through solids, liquids, and gases, but it does so at different speeds. It can rustle through trees at 770 MPH (miles per hour), echo through the ocean at 3,270 MPH, and resonate through solid rock at 8,600 MPH.

The smallest thing around is the atom, which has three main parts – the core (nucleus) houses the protons and neutrons, and the electron zips around in a cloud around the nucleus.

The smallest thing around is the atom, which has three main parts – the core (nucleus) houses the protons and neutrons, and the electron zips around in a cloud around the nucleus.